By Mary Hoover, SMCA Coordinator

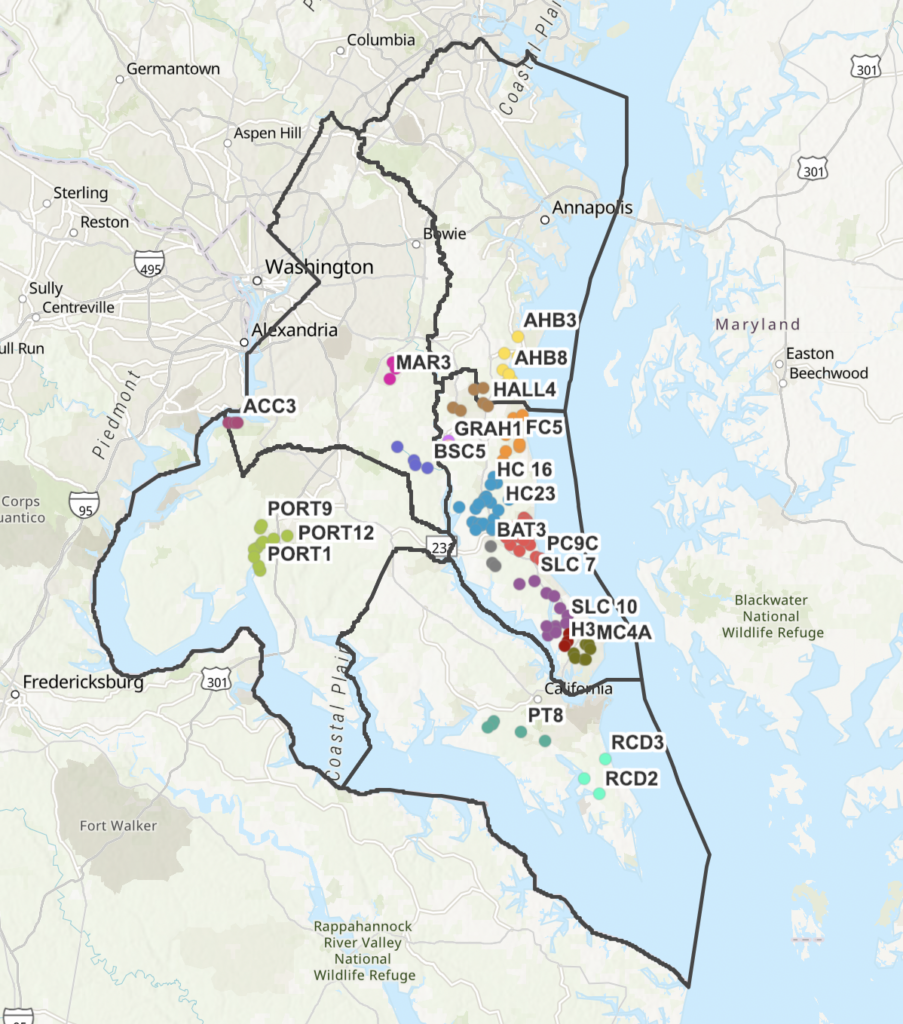

It was a mild and sunny April morning at the American Chestnut Land Trust (ACLT). Excitement and anticipation permeated the crowd of 30 volunteers, as Dr. Walter Boynton, a retired estuary ecologist from the Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, gave his yearly monologue and demonstrated proper water sampling techniques. Those gathered would shortly hike or drive to sites throughout Parkers Creek, Fishing Creek, St Leonard Creek, and Battle Creek to collect water samples for nitrate (NO23) analysis. This scene, however, conveyed only a fraction of the efforts happening throughout Southern Maryland. In all five counties, volunteers were preparing to traverse streams in the spirit of citizen science, with a record 128 sampling sites awaiting their attention. The 2024 Water Quality Blitz was underway.

Organized by the Southern Maryland Conservation Alliance (SMCA), the Water Quality Blitz is an annual citizen science initiative focused on sampling nitrogen levels in streams. Nitrogen, one of the primary pollutants in the Chesapeake Bay and the Patuxent River, is a key nutrient to manage. Fortunately, it is also a relatively easy nutrient to monitor. Research indicates that conducting spring sampling for nitrogen once a year yields accurate estimations of average yearly nitrogen in streams (Weller & Jordan, 2020). This method allows for the substitution of multiple yearly samples with a single, comprehensive sample, offering a cost-effective and time-efficient approach to nitrogen monitoring, particularly suited for non-profit organizations like those affiliated with SMCA.

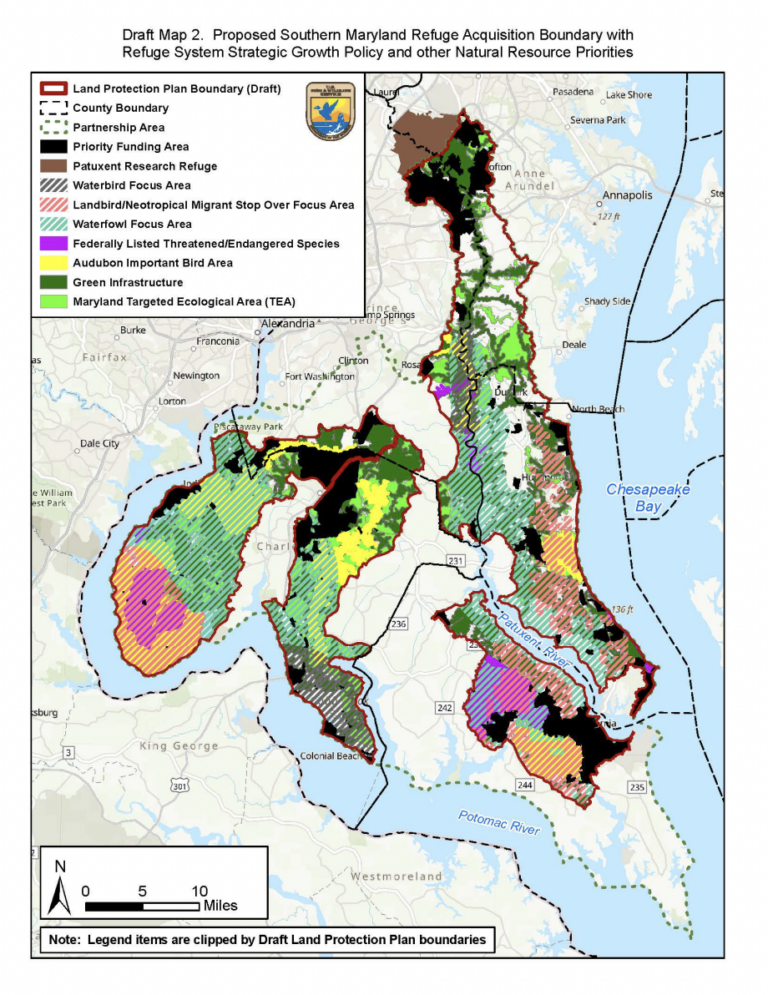

The Blitz began in 2017 as a local effort by ACLT for the Parkers Creek watershed. As ACLT began to establish friends groups in other watersheds, however, the Blitz expanded to include sites in these other watersheds. In 2023, the Blitz became a regional effort, with the participation of groups from the newly-formed Southern Maryland Conservation Alliance, with sites in four out of the five Southern Maryland counties. In 2024, the Blitz reached new heights with participation from all five counties, namely Anne Arundel, Prince George’s, Charles, Calvert, and St. Mary’s. With a remarkable 128 sampling sites (right)—a significant increase from the previous year’s 95 sites—the 2024 Blitz underscored SMCA’s collective commitment to environmental stewardship and science-based action.

The 2024 Blitz expansion came at a highly opportune time in the history of Chesapeake Bay. Despite decades of clean up efforts guided by the Chesapeake Bay Program, progress has fallen short of expectations. In May 2023, a group of scientists known as the Scientific Technical Advisory Committee (STAC) addressed the shortcomings of the Program in a report titled “Achieving Water Quality Goals in the Chesapeake Bay: A Comprehensive Evaluation of System Response” (CESR). One of the most notable of the report’s recommendations was the call to emphasize restoration in shallow waters of the Chesapeake Bay Watershed in addition to the deep channels (Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC), 2023). This emphasis on shallow waters echoes the goals of SMCA’s annual water quality blitz, which targets shallow, non-tidal streams and smaller tributaries of the watershed.

A science-driven approach to restoration and a strategic focus on shallow waters stand as pillars in both Chesapeake Bay restoration and the Water Quality Blitz. Additionally, SMCA recognizes a vital third element necessary to achieving Bay cleanup goals: citizen involvement. Bay restoration is an immense task that governments neither can nor should tackle alone; it requires the active participation of communities. Citizens of watersheds not only possess local knowledge and personal stake in environmental protection, but they also provide essential boots on the ground to monitor streams. The monumental feat of sampling 128 sites during the 2024 Blitz would not have been possible without the aid of over 50 local volunteers trekking through Southern Maryland streams and meticulously filtering samples. For this reason, we extend our gratitude to those who generously volunteered their time to this important endeavor. Our volunteers’ enthusiasm for the Bay and their commitment to citizen science serve as much-needed inspiration amidst news of Bay Program shortcomings and overall climate fatigue. In mobilizing communities around citizen science, the Blitz continuously reminds us that the Chesapeake Bay is not beyond saving. Each year offers reassurance that the grit and optimism of local citizens remain buoyant forces, propelling us toward a brighter future for the Bay.

References:

Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee (STAC). (2023). Achieving water quality goals in the

Chesapeake Bay: A comprehensive evaluation of system response (K. Stephenson & D. Wardrop,

Eds.). STAC Publication Number 23-006, Chesapeake Bay Program Scientific and Technical

Advisory Committee (STAC), Edgewater, MD. 129

Weller, D. E., and T. E. Jordan. 2020. Inexpensive spot sampling provides unexpectedly effective indicators of watershed nitrogen status. Ecosphere 11(8):e03224. 10.1002/ecs2.3224

Weller, D. E., and T. E. Jordan. 2020. Inexpensive spot sampling provides unexpectedly effective indicators of

watershed nitrogen status. Ecosphere 11(8):e03224. 10.1002/ecs2.3224

Weller, D. E., and T. E. Jordan. 2020. Inexpensive spot sampling provides unexpectedly effective indicators of

watershed nitrogen status. Ecosphere 11(8):e03224. 10.1002/ecs2.3224W