This blog was written by Kirsti Uunila and Carl Fleischhauer and depended upon Shelby Cowan’s research at the National Archives. An early version of this draft benefited from advice from the ACLT board members Darlene Harrod and Shirley Knight.

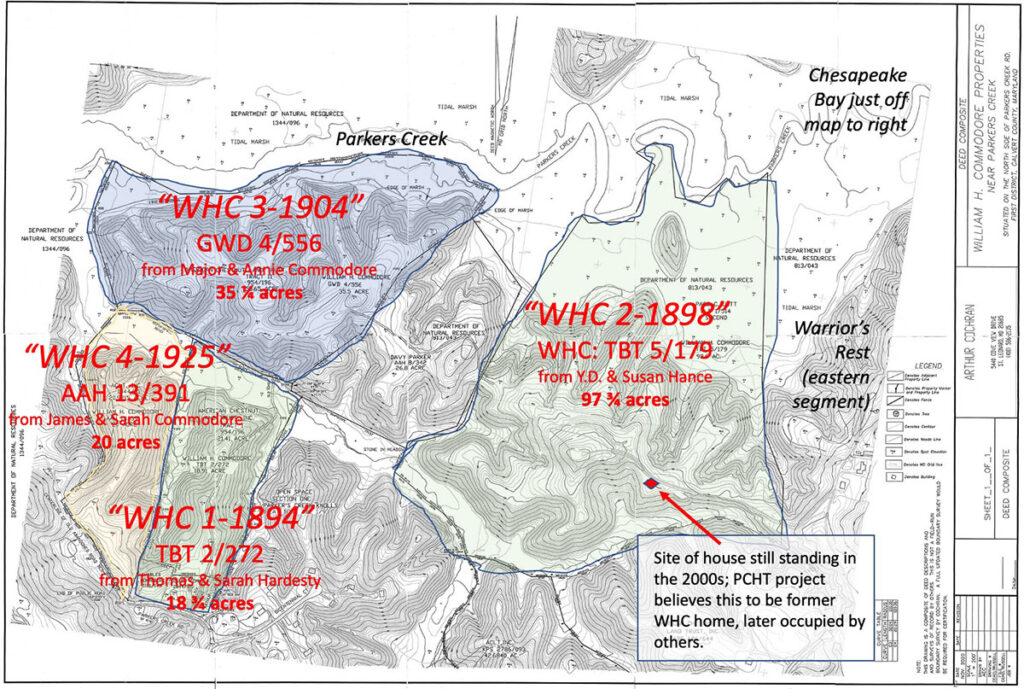

ACLT’s Parkers Creek Heritage Trail project has assembled information about several African American families in the Parkers Creek area. One example is the family led by William H. (1861-1938) and Suddie Commodore (1871-1951). Her name is sometimes spelled Sudie or Saddie in records; her maiden name may have been Boom, also spelled Boome. As the map in this blog indicates, their land flanked Parkers Creek and, in part, occupied the northwestern segment of what is today called Warriors Rest. Research continues and new findings may lead us to adjust the account that follows.

William H. Commodore was almost certainly the grandson of an enslaved couple and the nephew of a Civil War soldier. As late as the 1930s (and perhaps a bit beyond), the Commodores owned about 220 acres of land, most of which is now owned by the ACLT or the State of Maryland DNR.

William H. Commodore and his family mastered a range of interests and skills beyond the farming that was no doubt their main source of income. Census data for 1940 names two of William and Suddie’s sons, John and Willis, and identifies their occupations as “Laborer” and “Fishing Nets.” The latter is almost certainly a reference to their employment at Frank Richardson’s pound net operation at the mouth of Parkers Creek, a short walk from the Commodore home.

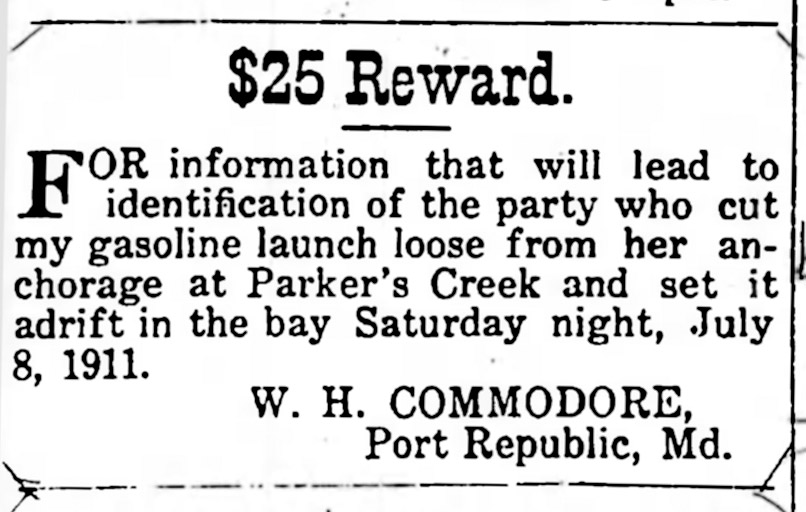

An earlier newspaper item hints at an earlier connection to local fisheries. The July 22, 1911, issue of the Calvert Gazette, carries William H. Commodore’s advertisement of a $25 reward for “information that will lead to identification of the party who cut my gasoline launch loose from her anchorage at Parker’s Creek and set it adrift in the bay Saturday night.” It is impossible to be certain from this notice, but the amount of the reward and the terminology “gasoline launch” suggest that this may have been a workboat for use in commercial fishing.

The occasional synergy between farming and Richardson’s pound net operation is expressed by a reminiscence from another fishing crew member. In a 1999 interview, Bill Tettimer told about going to the Richardson’s fishing shanty and net yard during an exceptional snow storm in the winter of 1941. “We went up there to mend twine,” Tettimer said, and “we was stuck in there for a week, and that Saturday night, we had to have three–the oxen–the Commodore boys, there was eight of ’em, had two oxen to get us out of that Parkers Creek. . . oxen pulling them two automobiles. . . Commodores owned the oxen.”

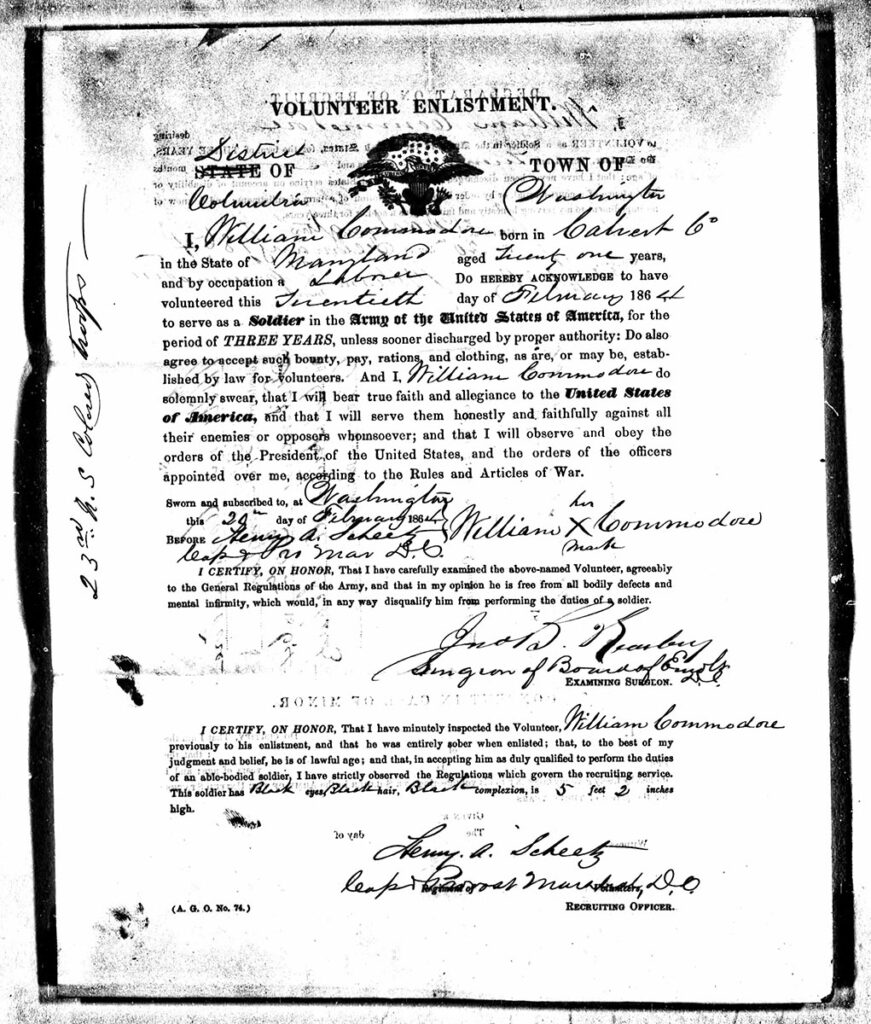

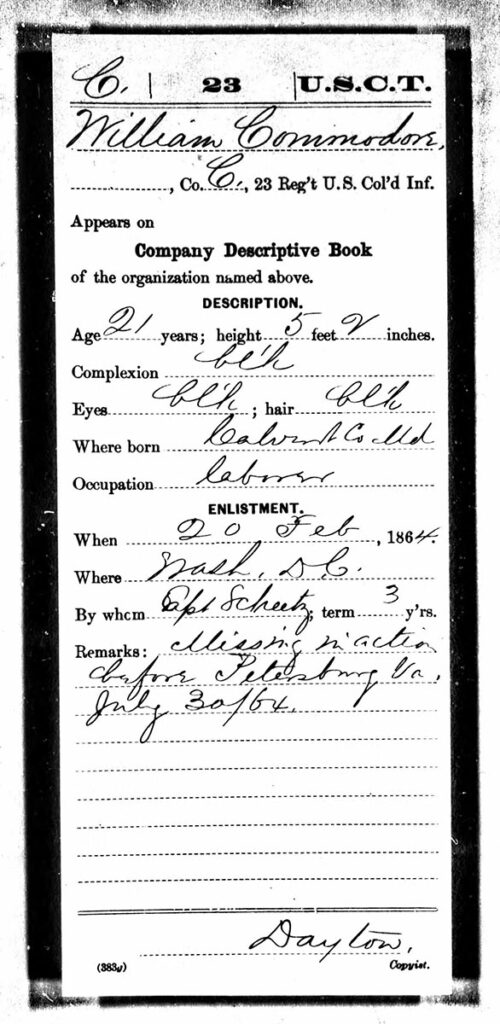

We cannot be fully certain of the connection, but the records of the 23rd Regiment of the U.S. Colored Infantry include service records for a man named William Commodore of Calvert County, who enlisted in February 1864 at age 21 and is listed as missing in action in July of that year. Images of the documents are shown below. We believe this to have been William H. Commodore’s uncle and one of his namesakes. We have not identified the Civil War soldier’s brother who would have been William H. Commodore’s father.

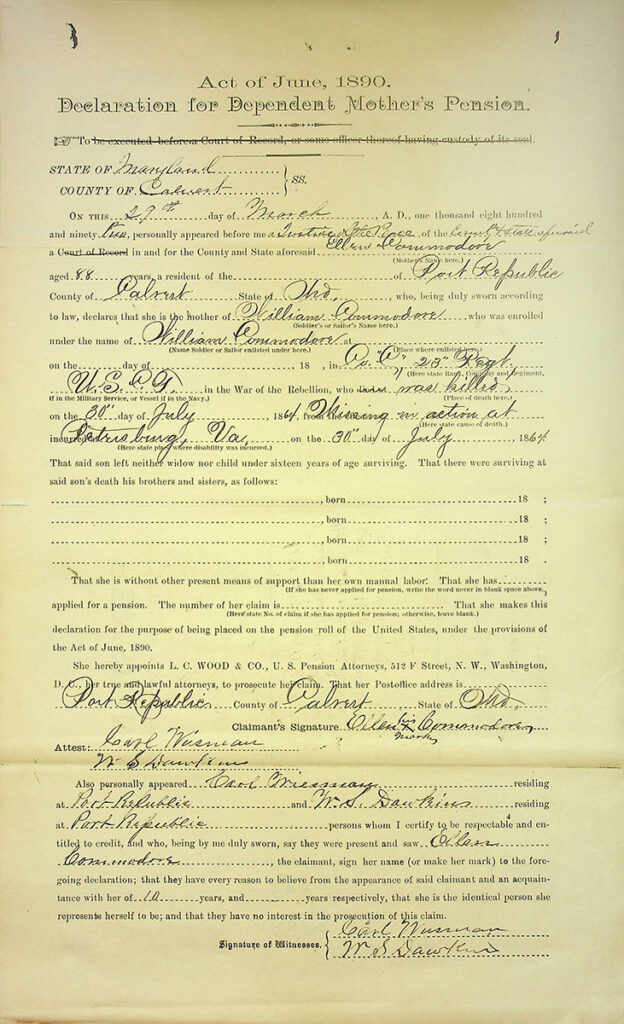

In addition to the U.S. Colored Infantry records, we base our account on two other forms of documentation: (1) pension records associated with the Civil War military service, and (2) an enumeration in the 1880 federal census.

The pension records chronicle an application process that lasted for more than twenty years. The earliest documents date from 1867, when a William Commodore appeared before a Justice of the Peace and testified that his son, William, died in action at Petersburg, Virginia on July 30, 1864, leaving no wife or children. A later census record tells us that this elder William Commodore was born in about 1820; his wife Ellen was born in about 1816. We believe that he was the grandfather of the William H. Commodore who is the main subject of this blog.

In 1892, as the pension case continued, three friends from the Parkers Creek neighborhood submitted affidavits. They were Alonzo Bell; Jeremiah Boots, identified as “Jerry” in other, unrelated documents; and George Boots. Jeremiah Boots stated, “I know that Wm Commodore, husband of Ellen Commodore is dead. He died in December 1881. I know this from the fact that I was at his funeral. I think he left about thirty-five acres of land which he left to his children at his death.” Boots also stated, “I knew William Commodore, son of Ellen Commodore, he died or was killed in the service of the United States. He was never married and left no widow or children. He was a son of Ellen Commodore. She has no means of support except what she can do herself and what anyone may give her.” George Boots also testified that William Commodore left no wife or children. The outcome of the case was that Ellen Commodore was awarded a pension and she collected $12 monthly between 1892 and her death on March 22, 1897.

William Commodore’s 1867 testimony includes information that is somewhat incidental to the pension claim, but critically important to the family’s history. Commodore testified that he and Ellen Commodore “were slaves of the same master and live on the same plantation as man and wife, and have so lived since the date of their marriage in the year 1823.” (The marriage date of 1823 is inconsistent with the couple’s ages in the census and was likely written in error.) Two White residents who knew the family supported the testimony: Samuel B. Wilson, given the title Captain, and Dr. Benjamin Owen Hance, who lived on land called Angelica, not far from Plum Point on Wilson Road. Although we have not yet identified the enslaver, we conclude that William and Ellen Commodore and presumably their children including William, the soldier, and perhaps two of their grandchildren were all enslaved on the same property by the same man or woman.

The second item that adds to our knowledge of the family and its circumstances is the 1880 census enumeration of the William and Ellen Commodore household. This listing identifies five of the couple’s grandchildren who were counted with them: William, age 19, whom we believe to be the William H. Commodore central to the Parkers Creek story; Mary, 18; Major, 14; Harriet, 11; and Robert, age 8. Emma Anderson, age 19, also lived in the household as a boarder and was a schoolteacher. The 1880 census makes no mention of the in-between generation, meaning the parents of the five grandchildren. Since William and Mary were born before the end of the Civil War, in 1861 and 1862 respectively, it is possible that they had also been enslaved with their grandparents and, perhaps, their parents.

This blog is part of the Parkers Creek Heritage Trail (PCHT) project, supported by funding provided by the Maryland Heritage Areas Authority, part of the Maryland Historical Trust in the Maryland State Department of Planning. The project will explore a wide range of topics, including aspects of African American history in the area. Although a work in progress, you may be interested in a booklet produced by the project entitled, “The African American Community of Parkers Creek, circa 1800-1960,” available here: bit.ly/PrkCrkCommBook. Researchers Kirsti Uunila and Carl Fleischhauer will be happy to receive comments or corrections if you have things to add or spot mistakes in the booklet. Meanwhile, we hope to produce an expanded version after we finish a related oral history interview project next year.