Introduction

This blog was researched and written by Beth Yoe Fiddler with the help of her sisters and brothers. As documented in the first section, Beth and her four siblings represent the ninth generation of this branch of the Yoe family to live in Maryland. They are also the sellers of the family farm to the ACLT, happy to know that the fields and woods they knew and loved will remain undeveloped forever.

Table of Contents

The Yoe Family in Calvert County: The First Nine Generations

First Generation

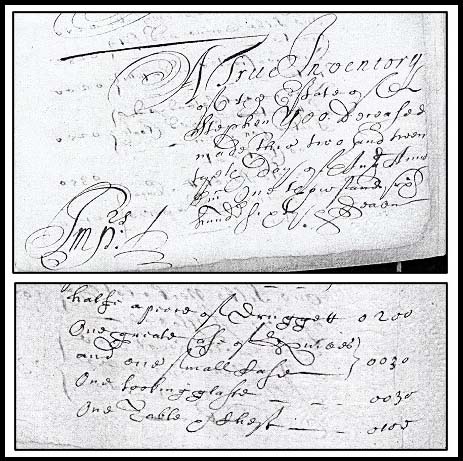

Stephen Yeo/Yoe, born circa1638 in England, died circa 1667 in Calvert County. The inventory of his estate included “four table forks,” then uncommon.

Second Generation

John Yoe, born circa 1666-1668, died 1733. His eldest son, Stephen, conveyed his interest in a tract of land that he had obtained from his grandfather, Stephen Yoe.

This conveyance establishes Stephen Yoe (died 1667) as the father of our lineage’s John Yoe. Over the years, the presence in Calvert County of a second John Yoe–born 1651, died 1686, and not related to Stephen–has led to some confusion. This second John Yoe (or Yeo) was a well-known cleric, almost certainly the first rector of Christ Church, then in Calverton on the Patuxent River, now located at Port Republic. The Reverend John Yoe moved away from Calvert County in 1677.

Third Generation

Robert Yoe, date of birth unknown, died circa 1761.

Fourth Generation

John Yoe, born July 29, 1750, died circa 1813. Among John’s six sons and three daughters by two wives was a son named Robert. Robert observed the enslaved Frisby Harris “acting as an officer” when the British burned the Calvert County courthouse in 1814. Harris had escaped his owners and joined the British fleet as it sailed up the Patuxent, en route to Washington, where the British burned the Capitol building and White House. (More about Frisby Harris here: https://bit.ly/42Blwyu.)

Fifth Generation

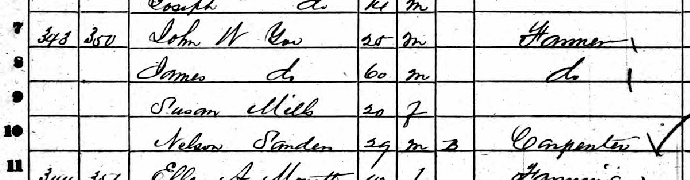

James Yoe, born August 28, 1795, date of death unknown (after 1860.) James married Ann Williams. The 1860 census shows James Yoe, age 60, and John Williams Yoe, age 25, farming together in Port Republic. Also living on the property at the time was an African American named Nelson Sanders, a free man with the occupation carpenter.

Sixth Generation

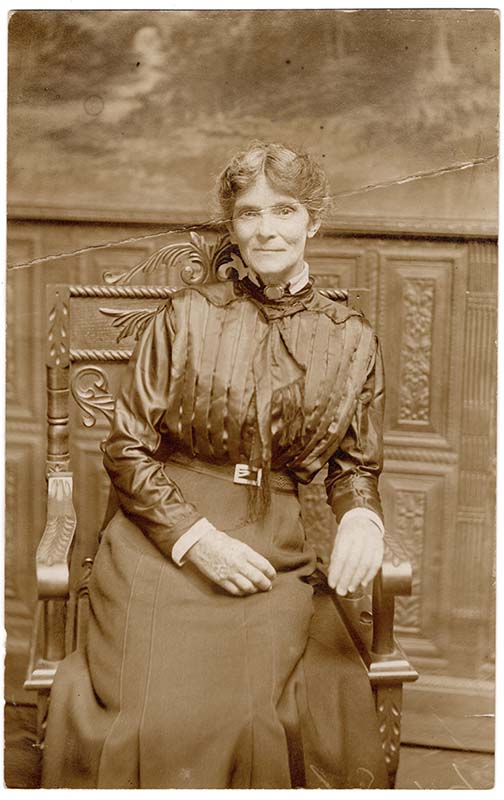

John Williams Yoe, born November 15, 1833, died January 26, 1901. He married Mahala Eugenia Holt (1857-1943) on January 21, 1879; she survived him.

Seventh Generation

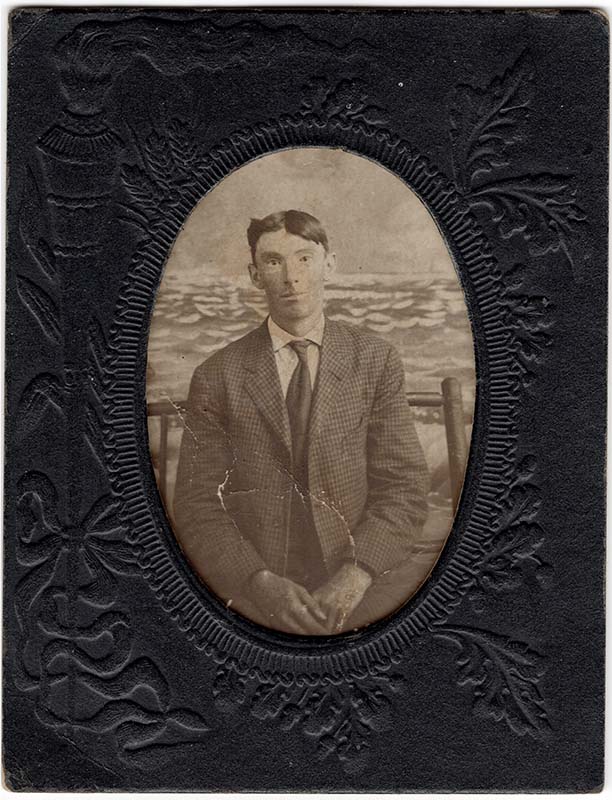

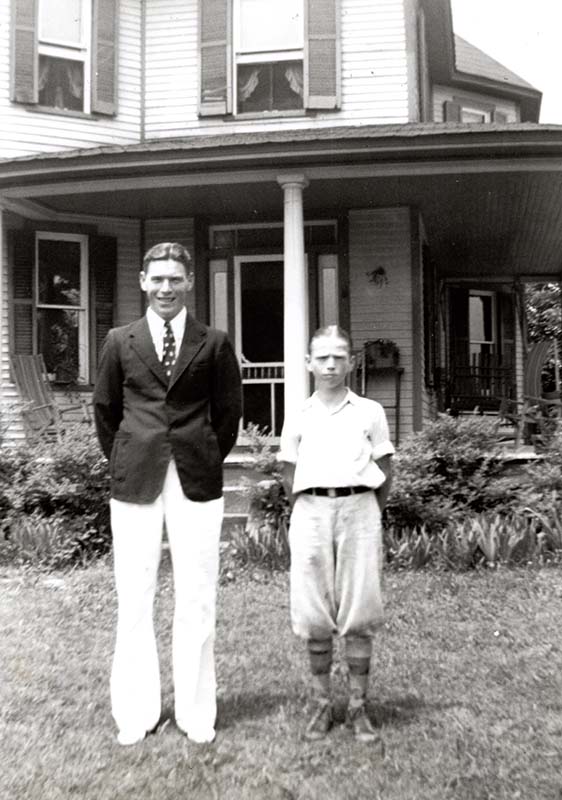

John Williams Yoe, born April 8, 1886, died June 5, 1964. John Williams Yoe and Elsie Mae Weems were married on January 20, 1909. Together, they had six children. They had been married for 55 years when John died. Elsie died December 31, 1978, at the age of 87. Both John and Elsie are buried at Christ Church, Port Republic MD. They are the grandparents fondly remembered in the statements that conclude this blog.

Eighth Generation

The eighth generation are John and Elsie’s six children. The eighth generation’s own children, now grown, provided the reminiscences in the last section of this blog.

Howard Philip Yoe was born in 1910. His first wife was Susanna Dixon Yoe. Susanna’s daughters from a previous marriage, Mary Jane Warren McMenamy and Carolyn Warren Gafner, recalled many happy childhood visits to the Yoe Farm. Howard and Susanna’s two children were H. Randolph Yoe, who died very young, and Pamela Yoe Hoffman, who also shared memories of visiting her Yoe grandparents on trips from Baltimore. Susanna died in 1955 and, some years later, Howard married Della Marie Yoe.

Mary Madeline Yoe was born in 1912. Madeline married George Fink, and they lived in Baltimore. They had one daughter, Shirley, who died in 2011. Madeline and George welcomed their niece, Pamela Yoe Hoffman, into their home, as she was still a baby when her mother died.

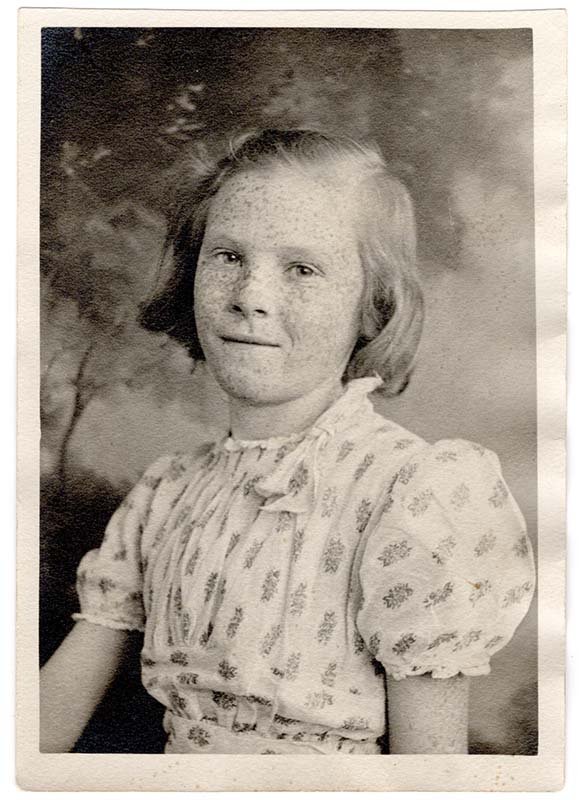

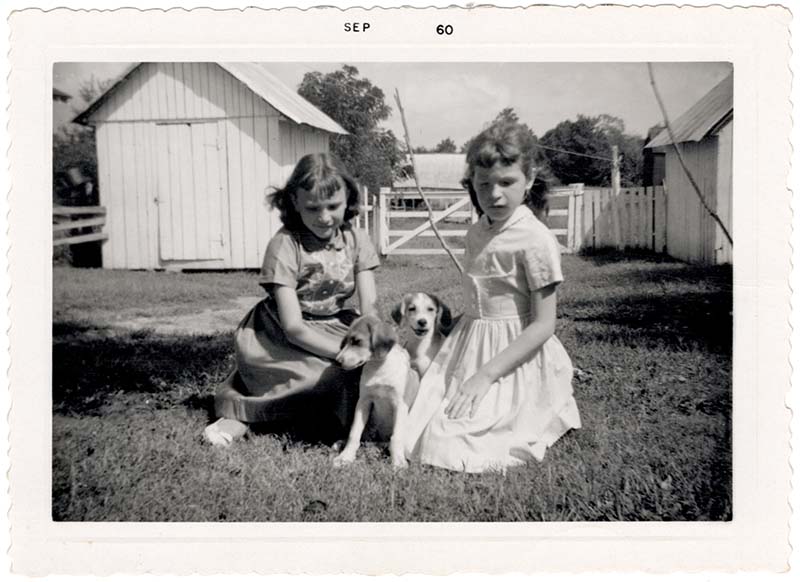

John Alvin Yoe, generally called Alvin, was born in 1914. Except for his World War II service in North Africa, Sicily and Italy, Alvin spent his entire life in Calvert County. He married Mae Elizabeth Gosnell in 1948, and they had five children: Elizabeth (Beth) Degitz Yoe Fiddler, Mary Ruth Yoe, John Williams Yoe, Marjorie Anne Yoe, and James Gosnell Yoe. These children lived just north of the Yoe Farm, a short walk across “the flat” from their grandparents’ home.

Betty Louise Yoe was born in 1916. She married Philip J. Trueschler, Jr. They lived in Baltimore and had no children.

Thomas Linwood Yoe, generally called Linwood, was born in 1922. He married Grace Gibson. They lived in Huntingtown and had no children.

Elsie Anne Yoe was born in 1929. The house on the Yoe Farm was her residence for most of her life.

Ninth Generation

The ninth generation is composed of the many children of the eighth-generation parents named above. As the grandchildren of the seventh-generation John Williams Yoe and Elsie Mae Weems Yoe, they provided the memories in the section titled Life on our Yoe Grandparents’ Farm, below.

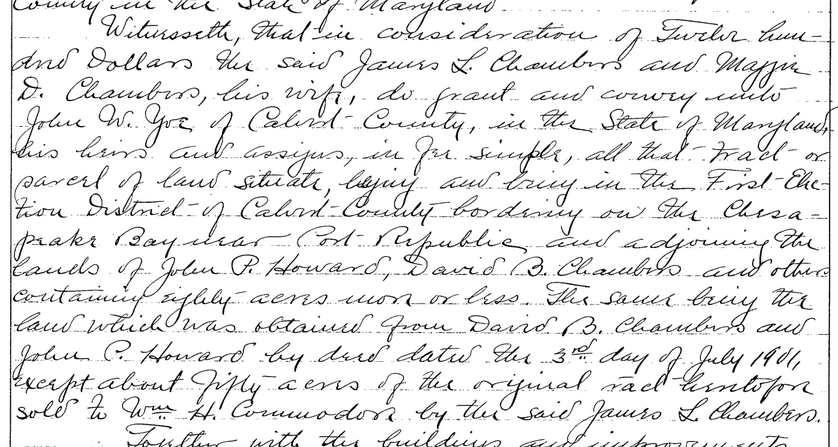

History of the Yoe Farm

Determining a historical chain of title for property in Calvert County is complicated by two disastrous fires in 1882, destroying the courthouse in March, when some records were saved, and then destroying the temporary storage building in June. The information that remains is characterized by vague descriptions and fluctuating acreages. Meanwhile, research continues to determine with certainty which colonial-era patent or patents underlie today’s Yoe Farm. One segment is almost certainly part of a tract known as Horse Range, patented by James Ayling in 1723.

By 1901, when John Williams Yoe died, he had lived on the Yoe Farm since 1860. He was survived by his widow, Mahala Eugenia Holt Yoe, and five children, including a son also named John Williams Yoe (1886-1964, the authors’ grandfather). Tobacco was the farm’s cash crop from the 1860s until the mid-1980s.

After John Williams Yoe’s death in 1901, there was a legal dispute between his siblings for ownership that lasted until 1913.

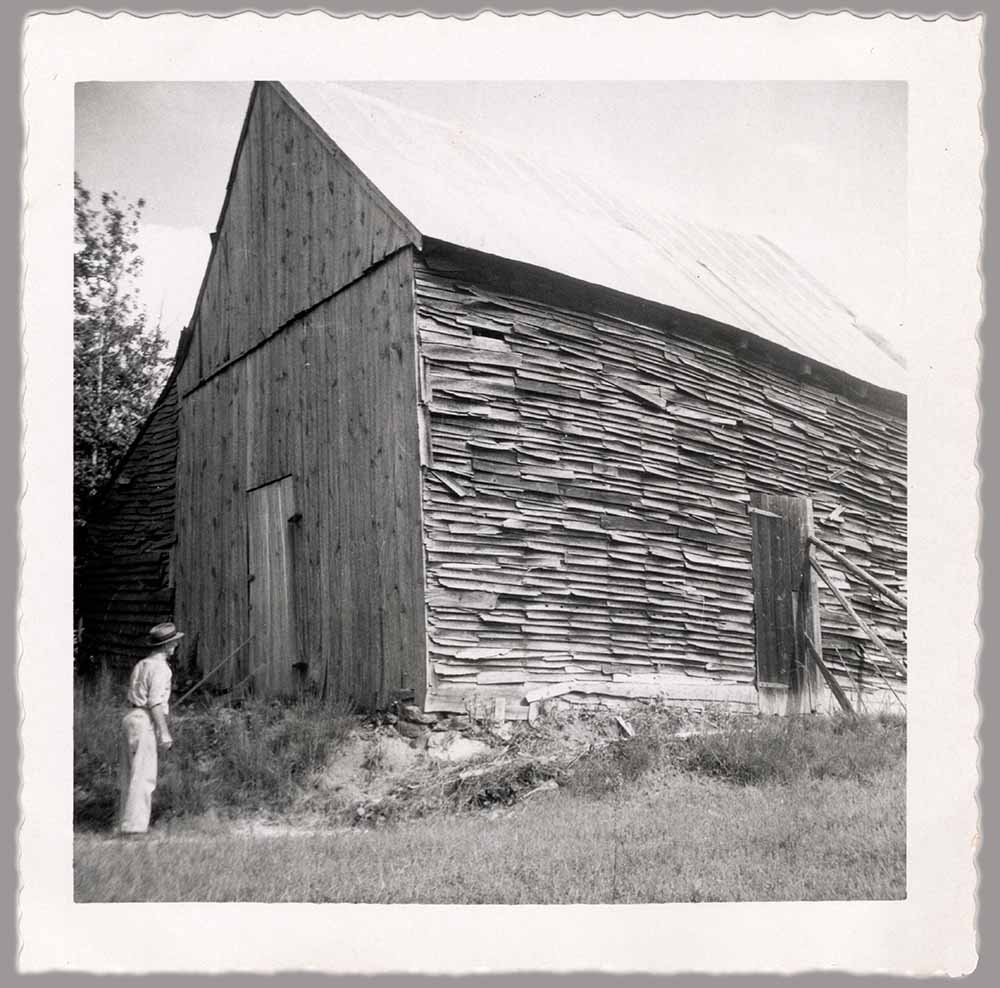

In 1909, during this familial dispute, John Williams Yoe (born 1886) married Elsie Mae Weems. The farm was still occupied by the family, however, and that is where John and Elsie began their married life. The first of their six children was born in the “old house,” a handsome timber-framed building that still stands today, although in very deteriorated condition.

The timber-framed “old house” as it stands today, about 200 yards west of the “new house.” Construction details support the mid-19th century date, including a large stone fireplace that, like the house itself, is now deteriorated. Photographs 2022 by Carl Fleischhauer.

By 1911, in part to protect against the risk of loss of the farm, John purchased 80 acres on the Chesapeake Bay, part of which is today’s gate D neighborhood in Scientists’ Cliffs. John and Elsie’s second child was born in “the Bay house.”‘

As it happened, the bayfront “hedge” property was not needed. In 1913, the court-appointed trustee sold the Yoe Farm to a third party and, in 1914, he sold it to John Williams Yoe, bringing the property back into the family. Yoe sold the bayfront 80 acres in 1915.

John and Elsie’s children have had a “family debate” as to whether their third child, John Alvin Yoe, generally called Alvin, was born in the “Bay house” or the “old house” but by 1916, the Bay property had been sold and their fourth child was born in the “old house.” The “new house” was built circa 1918, and the two youngest children of John and Elsie were born there.

Regarding tobacco, the farm’s peak production occurred before, during, and just after World War II. Tobacco was grown on ten or twelve acres, yielding a crop that often filled the family’s four barns plus a fifth barn they rented just down the road. The decision to stop growing tobacco was made in 1985 or 1986 by John Williams Yoe’s grandson Alvin (eighth generation). Alvin’s decision reflected the very recent death of his wife Elizabeth, and his reaching the age of 71. The family let the land lie fallow for two years and then began leasing the fields to farmers who cultivated small grains, corn, and soybeans.

After John Williams Yoe died in 1964, his heirs did not divide the farm, only selling shares among themselves. Thus, the Yoe Farm remained essentially as it had been until it was purchased by the American Chestnut Land Trust in 2022.

Life On Our Yoe Grandparents' Farm

These memories were written by the grandchildren of John Williams Yoe and Elsie Weems Yoe. We loved our grandparents–and we cherish our memories of them, their home, and their farm.

The oldest of us remember times before the current house had electricity, indoor plumbing, or central heating. Some of us lived in Baltimore, and so coming to the country for a visit was a great adventure.

- Mary Jane McMenamy recalls that Grandmother Yoe would put wood in the big stove for cooking; it made the kitchen very cozy. Dinners included vegetables from her garden and biscuits made from scratch. The most fun was watching her chase the chicken that was to be our dinner.

- Carolyn Gafner wrote that at night, we would huddle by the wood stove in the kitchen. Our light was an oil lamp. There was an outhouse for use in the daytime; there were porcelain potties with lids for nighttime. Each bedroom also had large ceramic pitchers with matching large bowls, for washing up.

- Mary Jane and Carolyn both remember that on Saturday evening, the bathtub was brought into the kitchen, water (drawn by bucket from the well in the side yard) was heated on the stove, and one by one each family member took a turn to bathe. The men filled a basin with warm water from the stove and shaved on the glassed-in back porch.

- While Beth was too young to remember this event herself, she does remember being told, quite often, the story of her parents’ first trip to Prince Frederick, about three weeks after she was born. It was a rainy, chilly April day, and Grandmom, who had been enlisted as an experienced babysitter, became concerned that tiny Beth, who weighed just over five pounds, would take a chill in the house. At that time, the kitchen stove was still a wood stove, and the oven door opened out into the kitchen. To keep Beth warm, Grandmom tucked her swaddled body into her roasting pan and set the pan on the oven door! Fortunately, it was not a Sunday, and so the roasting pan was not occupied by a chicken. Grandmom was occasionally heard to say, “None of MY babies was that small!”

- Every grandchild recalls that even after the house had indoor plumbing, Grandma or Grandpop would draw water from the well and we would drink the icy cold water from a tin dipper—a refreshing treat on a hot summer evening. Those of us who lived next door and ran around mostly barefoot and bare legged all summer also recall the rivulets of cool water running down our legs, streaking our dust-covered shins.

- John, the namesake of his grandfather, vividly recounts the story of his first tobacco crop: When I turned six in 1961, Grandpop decided I should have a direct stake in that year’s tobacco crop. A small field, no more than a quarter acre, was “Johnny’s Field” that year. August rolled around and the harvest crew made their way to the fields adjacent to mine. Disappointed that no one was assigned to my field, I took matters into my own hands. Retrieving a small hand saw from the red F-250, I started sawing my crop down. This got a big laugh from everyone, as normally tobacco is chopped down. Grandpop said kindly that my field was not quite ready for harvest, and I could put my saw away for the day. The next spring, my crop fetched $75 at the market, a small fortune to an almost seven-year-old.

- Pam remembers that Grandmom would putter around the kitchen, singing “What a Friend We Have in Jesus.” Pam continued, Grandmom always wore a plaid housedress, an apron, stockings rolled just above her knees and held in place with elastic garters, and black oxfords, which I think were called Enna Jetticks. Sometimes she had a picture of her oldest, my father, pinned to her dress. It was the pin he had worn as an air raid warden during WW 2. One afternoon, she went out to the hen house and came out with a large hen under her arm and went into the kitchen. I shuddered in disbelief because I knew what was going to happen. Sure enough we had fried chicken for dinner that night.

- There is no one who remembers leaving Grandmom’s house hungry and those who enjoyed her Sunday or company dinners all praised her cooking. However, those of her grandchildren who lived next door appreciated her generous snack policy, whether it was a ham sandwich cut diagonally or across, to your preference, or an offering of candy from her pantry. Grandpop liked yellow cake with chocolate frosting, and it was kept in the refrigerator. That, too, was a treat.

- Margie, too, recalls drinking hot Lipton tea and ginger snaps at the red-trimmed kitchen table. She remembers, too, singing familiar church hymns from memory with Grandmom, who would praise her singing ability.

- Snacks were not limited to her grandchildren, however. Beth recalls a warm summer afternoon when Grandpop was working, hoeing tobacco, in a field far from the house. Grandmom gave her a lidded mason jar filled with water and lemon slices, and a small brown bag with gingersnaps, with instructions to take them to Grandpop. She was reminded not to eat any of the cookies on the way to the field as they were for her “Johnny” to “settle his stomach.” When she arrived at the field, Grandpop opened the bag of gingersnaps and immediately handed her one, which she of course ate. When she got back to the house, Grandmom gave her gingersnaps, too, even though she explained that she had already had one.

- Beth also remembers that in the late afternoon, she would sit on the kitchen steps and hold a mirror for Grandmom, who “fixed myself up for Johnny” before Grandpop came home for supper. Grandmom changed her apron, and after a touch of Pond’s Cold Cream, eyebrow pencil, rouge, and lipstick, and a fresh twist of her long hair into a bun, she looked pretty and happy.

- After Grandpop’s death in 1964, Grandmom enjoyed having one of her nearby grandchildren spend the night for company. John recounts: I remember her making sure I had a proper snack of Pepsi and fudge stripe cookies while doing homework, which she called lessons. Lessons completed, I would read every word of the Evening Sun sports section. On some winter nights, even with the house heated, the wind would rattle the windows and seemingly come right into the bedrooms. Grandmom always prepared a hot water bottle to keep at my feet on those coldest of nights.

- Those of us grandchildren who lived nearby also are able to recall a few events on the farm which we have only shared with each other. Our parents never knew the particulars, and since the statute of limitations may not have run out on these misadventures, we will not share them here! They were, suffice it to say, great bonding experiences as we were always able to resolve the situations on our own!

- Beth adds, too, that while some memories are of specific events, there are some others that are snippets, consisting of moments of remembered light, or never to be forgotten smells. The smell of tobacco lingers in barns that have not held tobacco for years, or is infused in the antique, crooked tobacco stick that now serves only a decorative purpose. Shafts of light still fall, slanted, through the walls of the corn crib and the meat house. Larger rays of light create patterns on the hard-packed dirt floors of the barn. Fingers still feel the hard kernels of field corn on the cob, and the sound of the kernels falling as the corn was shelled into a metal pan, to feed the chickens. There is the feel of a scratchy wool cardigan sweater against the tender skin of a little girl sitting on her grandfather’s lap. There is the feel of the velvet dust that rose between bare toes on the family’s evening walks to the old barn, to close its doors, or inspect the fields.

- Then there are the more recent memories. Mary Ruth shares: In the 1970s, I stood with Daddy at the edge of “the flat,” the long, broad swatch of fields that lay between our house and that of our grandparents, stretching back to poplar, pine, and hickory woods. Our backs to Route 4, we watched my brothers plant row after row of tobacco in the early June evening. As shadows began the lengthen, Daddy turned to me and asked, “Do you know why I farm?” I could tell a rhetorical question when I heard one, so I waited. His answer was not what I expected: “I farm for the curve of the trees against the sky.” His eyes shifted to the field, and his voice shifted gears, barking out an order to my brothers, “Get that tractor back in line.”

These memories are preserved in the hearts of all the grandchildren who, whether visitors from the city or living right next door, were privileged to experience life on the farm. With the acquisition of the Yoe Farm by the American Chestnut Land Trust, we are delighted that “the curve of the trees against the sky” has been preserved for generations to come.