By Kassandra Patrick, Chesapeake Conservation Corps Intern/Double Oak Farm Manager

Our food systems are under threat, and our food systems are threatening us. Threats to us come from agriculture’s greenhouse gas emissions, but climate change caused by the emissions threaten agriculture as well, and by extension all food systems, through catastrophic weather changes. Luckily, agriculture has the potential to reverse its own trend of releasing emissions by making farming more ecologically friendly. Changing farming practices across the globe to incorporate perennial crops, cover crops, minimal tillage, and other sustainable practices would not only sequester more carbon but also improve soil health and food production[1].

Changing a whole world’s worth of farming practices is already a near impossible task, but what makes things worse is our current food system, which does not support farmers trying to adopt these practices. Farming careers are undervalued by society, leading to interested young people being discouraged from going into the field and people who do work in the field being subjected to poor working conditions[2], low pay[3], and little to no benefits[4]. I love agriculture, and I would love nothing more than to farm for the rest of my life in a way that serves the Earth and the communities around me. If I thought that it was possible for me to start farming as a career and have good working conditions, a living wage, and benefits, I would have already been farming while I was still attending college, gaining the experience to continue in the field as I worked toward my degree in Environment and Sustainability. I may have even chosen to focus my major electives around agriculture and food systems, but farming as a career path just did not seem feasible at the time, especially knowing I would be graduating with debts to pay. Luckily for me, I did end up finding a way to start farming by coming to ACLT. Becoming the Double Oak Farm Manager has not only allowed me to start gaining the valuable experience necessary to improve as a beginning farmer, but also showed me the inherent value of stewarding the land one farms.

As things stand, land is mostly seen through its ability to be exploited, leading to prime agricultural land being degraded or developed for housing, utilities, and other buildings before a single crop can be grown. Food systems are disconnected from the people they feed, leaving them incredibly vulnerable to disruptions to supply chains. Food that can not be moved goes bad and becomes food waste, and people facing food insecurity go hungry even when there is enough food produced to feed them. Despite the above systemic issues impacting the food system, a lot of public pressure has been directed towards farmers[5]. Farmers are told that their practices are hurting the planet, and that they need to change and be more sustainable or regenerative, which means different things depending on who is asking. When so many definitions of “sustainable agriculture[6]” and “regenerative agriculture[7]” exist, what are we asking from our farmers, and are the changes we’re asking for feasible?

The definitions of “sustainable” and “regenerative” seem to constantly morph. There are widely accepted aspects of both, but there is no standard that says any aspects must be included[8]. Therefore, rather than attempt to craft a universal definition, I aim to argue for what I believe “sustainable agriculture” and “regenerative agriculture” ought to mean. Sustainable agriculture ought to mean farming to sustain public health, environmental health, and farmers’ financial health. Sustaining public health goes beyond reducing greenhouse gasses. Nutrients in modern food have been dropping since 1950[9], but since food pricing is normally based on calories, farming food with higher nutritional value isn’t valued in the market. Environmental health includes issues of climate change and biodiversity. The UN Environment Programme identified international food systems as the main driver of global biodiversity loss due to habitat loss when land is cleared for farming[10].

To solve the first two issues, sustainable profit is key because directing our money toward sustainable agriculture collectively assigns worth to ethically grown, nutritious produce; when our money is put toward resilient food systems, the systems can continue to provide for our communities during times of economic hardship and supply chain shortages. All farmers, whether they own land or work on a farm, deserve fair, livable wages and healthcare.

If separating the term “farmer” from “land owner” confuses you, it’s likely because the two have been synonymous in America for decades now. Not Our Farm, a non-profit organization that represents people who have chosen farming for their career but do not own land, has interviewed many farmers currently employed as farm workers, farm employees, members of farm crews, farm managers, and apprentices and interns and asked them who should be considered a “farmer[11].” Quotes from the farmers interviewed point out that the terms “farmer” and “farm worker” perpetuate a class difference and power imbalance between agricultural landowners and people who work for them, that sometimes landowners do not personally farm their land, and that gatekeeping of the term “farmer” is often said to be based on years of experience despite immigrant farmers with years of experience being labeled as “unskilled labor.” Nomenclature aside, many of the farmers interviewed spoke of harrowing experiences with workplace harassment, lack of access to potable water and bathrooms, and, ironically enough, food insecurity. These experiences were and are not exclusive to large industrial farms, but they can not be completely blamed on the farming industry either. The devaluing of the work required to produce food creates situations where farmers who don’t own farms contribute valuable, skilled labor yet still go unprotected by minimum wage laws.

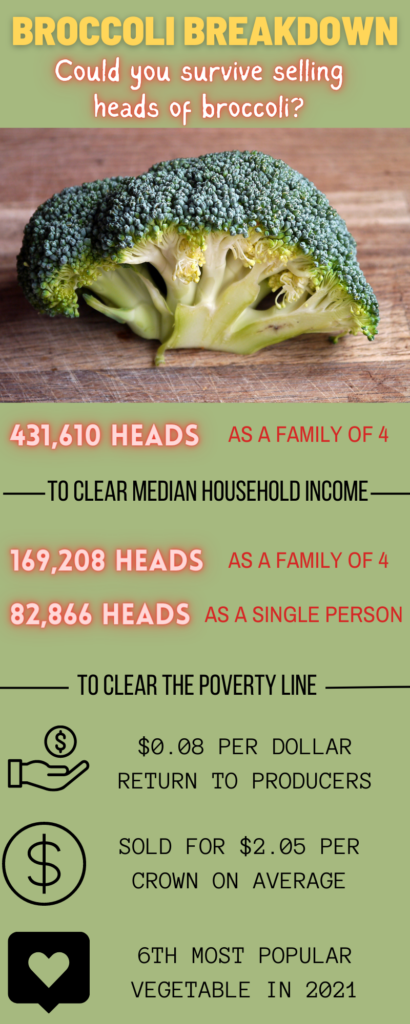

On the land-owning farmers’ side of things, profit margins are incredibly slim and getting slimmer as input costs continue to rise. Research on global farming economics has shown that farmer owners receive an average of 27% of what consumers spend on food if the food is sold and consumed in their home country, and the percentage becomes lower if the food is exported, which it often is in the US[12]. In fact, the same 2021 study found that the average return in America is much lower than 27% at an average of 9%[13]. The American Farm Bureau Federation reports an even lower rate of return of only 8 cents per dollar a consumer spends[14].

To put into perspective just how tight a profit margin that is, I ask one question: Could you survive selling heads of broccoli? Broccoli is a high value crop rated as the 6th most popular vegetable as of October 2021. A single head of broccoli, regarded by the USDA as crown cut broccoli, can sell for as much as $2.99 a crown, with the average price across the US being $2.05. That means that just to get above the federal poverty line for a single person, you would need to sell 82,866 crowns, and if you’re supporting a family of four, that number increases to a whopping 169,208 crowns. It bears repeating that this is just to clear the poverty line. If you want to clear the median household income with your broccoli, you’d need to sell 431,610 crowns. Granted, this 8 cents assumption takes into account wages for labor, so a farm owner may be able to make more by hiring only the bare minimum of employees and paying the lowest wages possible, which leads to the exploitation of employed farmers as described above. Costs of production are also taken into account, but referring back to the fact that the costs of inputs are increasing, lowering production costs simply may not be an option. This leaves little to no money, and likely little to no time, to invest in adopting sustainable practices. Rather than sustain these trends, we should want to change them. Where do we go from here to create a better agricultural system for these farmers?

Enter regenerative agriculture, which ought to mean farming to restore and improve public health, environmental health, farmer’s lives and livelihoods, and the culture of farming. The American idea of agriculture is dominated by the idyllic vision of small farms centered around the family unit, but this vision is only one way of farming, rooted in cultures in large part due to colonialism. In his Keynote speech for the 2023 Pasa Virtual Conference, Col Grodon details the history of farming in his home country of Scotland, describing how the invading British forces dispossessed indigenous people (in this case, the Gaelic people) from land with the excuse of “agricultural improvement” to institute British family controlled farms. Patterns of colonialism leading to land being taken from indigenous groups are observable in every colonized country, but before those events, land was still being managed to produce food. According to Col, in the case of the Gaelic people, the land was often managed communally with no private ownership. The consequence of colonizing countries enforcing their model of farming onto new areas was that colonizers farmed while culturally disconnected from the previous history and cultures of the land they were farming, meaning they lacked an essential motivation to foster land stewardship. Regenerative agriculture’s fourth goal is to recreate those cultural connections. In the words of Jason Gerhardt, another Pasa conference speaker who presented on Community Action Farming, “The real point of regenerative agriculture is to regenerate the culture of agriculture.” Whether land is farmed by a family or communally, all farms need the support of the people they serve. Like the relationship between agriculture and climate change, the relationship is two-way. Cultural support for farmers leads people to care about the land and its management, protecting agricultural land and farmers’ access to it. Farmers who are integrated into a culture of agricultural appreciation can have a dialogue with the people they feed about community needs and the farming practices used to make their products, which creates trust in the farmers’ produce and an appreciation of their work, ultimately leading to a dedicated customer-base that will be less phased by higher prices that internalize the full cost of farm production.

How do we rebuild the culture of agriculture? Firstly, we restore the land. Once again, when I say “restore,” I am referring to more than just ecological restoration. To truly restore the land, in the words of Col, “we must re-story the land.” We need to reconnect the stories and traditions of the landscape with the people living on it, cultivating their appreciation of the land and stimulating their imagination with ideas for a future in harmony with the land. Re-storying also serves to connect people within a community through a shared local culture. Secondly, we empower communities to create robust local food systems. Reconnecting people not only to their neighbors, but also to their food and the land that they inhabit is essential to rebuild the value of farming within American culture. Finally, we mobilize as communities in financial support of agricultural practices that serve the goals of the first two steps. The food systems these practices support will create long-term, fresh, nutritious, and local yields of produce and animal products that can meet community needs. These financial systems won’t be one-size fit all. In some places, there may be family farms, while in others, there may be community gardens. Some communities may utilize land protected by conservation easements, while others may participate in Co-op farming. Whatever way works best for the people involved is fine, as long as it stabilizes the profit of agriculture, allowing for farmer owners to live well despite incurring extra costs to farm in an ecologically and public-health conscious way, for farm-employed farmers to receive a living wage and other necessary benefits, such as healthcare, and for the community to directly benefit from the extra dollars they choose to spend on food grown and raised fairly and consciously.

To even begin changing the world’s worth of farming practices, we need to change the way farmers and their contributions are viewed. If we want to continue eating, we need to build our food systems to be more resilient, not only to climate change, but also to changes in our communities. If we are all to continue living on this planet, we need even more than just a planet where climate change has been mitigated. Lack of access to nature, pollution of water and air, and degradation of soils are only a few of the other environmental problems directly affecting public health that we can fix through regenerative agriculture. Regenerative agriculture recognizes that a food system is just as dynamic as the larger society that it serves. Building resilience in culture protects our land, in people protects public health, in ecosystems protect the environment, and in profit contributes back to the systems that people rely on outside of food to live healthy lives.

A transition is coming whether we want it to or not. 50% of agricultural land is set to change hands in the next two decades. 78% of young farmers do not come from farming families. The 2023 Farm Bill, legislation that sets federal agriculture, nutrition, conservation, and forestry policy every five years, is being discussed in the Senate right now, with public hearings still ongoing. Agriculture is going to change, and our food systems along with it. Luckily, if anyone has experience adapting to dynamic, ever-changing systems, it’s farmers. Whether beginning or experienced, young or old, owner or employee, farmers dedicate a large portion of their work to adapting, but they aren’t well prepared. They can’t be, because their level of preparedness depends in large part on the support from the people they feed. Yes, that means the government needs better agriculture policies, and we should support the policies that increase the capacity of farmers to adopt regenerative practices. Start by commenting on the 2023 Farm Bill, but comments can’t be our only collective action. The best thing that all of us can do to create change is to buy local. It’s the key action to create the financial conditions for regenerative agriculture and resilient food systems. The second best thing we can all do is grow some of our own food. This is for the sake of protecting ourselves from the next break in the global food chain, understanding the time commitment and skilled labor of farmers, and creating a personal connection to the land literally in our own backyards. These actions will defend our food systems from threats of all nature, from climate change to pandemics, and they will demand that our food systems no longer threaten our health and instead increase our quality of life. If change is inevitable, then let’s take a lesson from our farmers and grow into it.

[1] “Soil-Based Carbon Sequestration.” April 15, 2021. MIT Climate Portal. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://climate.mit.edu/explainers/soil-based-carbon-sequestration.

[2] “Resources.” 2021. Not Our Farm (blog). October 22, 2021. https://notourfarm.org/resources/.

[3] Kelmenson, Sophie. 2022. “Between the Farm and the Fork: Job Quality in Sustainable Food Systems.” Agriculture and Human Values, October. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-022-10362-x.

[4] See note 2 above.

[5] Karst, Tom. “Growers Feel Shortchanged with Sustainability Efforts.” 2022. AgWeb. June 30, 2022. https://www.agweb.com/news/business/conservation/growers-feel-shortchanged-sustainability-efforts.

[6]Gambino, Chris. “Defining Sustainable Agriculture & Why That Matters.” Lecture, Pasa 2023 Virtual Sustainable Agriculture Conference, January 17, 2023.

[7] Johnson, Nathanael. 2019. “‘Regenerative Agriculture’: World-Saving Idea or Food Marketing Ploy?” Grist. March 12, 2019. https://grist.org/article/regenerative-agriculture-world-saving-idea-or-food-marketing-ploy/.

[8] See note 7 above.

[9] Lovell, Rachel. “How Modern Food Can Regain Its Nutrients.” 2021. Accessed February 13, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/future/bespoke/follow-the-food-test/why-modern-food-lost-its-nutrients/.

[10] “Our Global Food System Is the Primary Driver of Biodiversity Loss.” 2021. UN Environment. February 3, 2021. http://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/our-global-food-system-primary-driver-biodiversity-loss.

[11] Adalja, Anita. “Not Our Farm: Stories from Farmers Who Don’t Own Farms.” Lecture, Pasa 2023 Virtual Sustainable Agriculture Conference, January 17, 2023.

[12] Yi, Jing, Eva-Marie Meemken, Veronica Mazariegos-Anastassiou, Jiali Liu, Ejin Kim, Miguel I. Gómez, Patrick Canning, and Christopher B. Barrett. 2021. “Post-Farmgate Food Value Chains Make up Most of Consumer Food Expenditures Globally.” Nature Food 2 (6): 4??–??. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-021-00279-9.

[13] Yi et al.“Post-Farmgate Food Value Chains Make up Most of Consumer Food Expenditures Globally.” 4??

[14] “Fast Facts About Agriculture & Food.” 2021. American Farm Bureau Federation. Accessed February 10, 2023. https://www.fb.org/newsroom/fast-facts?token=H0IEw1v7wfq7RwDCypu3W-Vm5E_CupKz.