The Miraculous Journey of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds

By Judy Ferris, Master Naturalist & Guest Blogger

As summer heats up, you have probably noticed the arrival of hummingbirds. Here on the east coast, we typically see only one hummingbird species – the Ruby-throated Hummingbird. Just like songbirds, Ruby-throats migrate each spring and fall.

Most Ruby-throated Hummingbirds over-winter in southern Mexico, Central America, and as far south as Panama. Their winter sojourn in the tropics, however, is not exactly a relaxing vacation. Not only must they compete with other Ruby-throats, but other hummingbird species are present as well. In Panama, for example, there are as many as 59 different hummingbird species to complete with. (Johnson 2019) No wonder these little creatures are always ready for a fight!

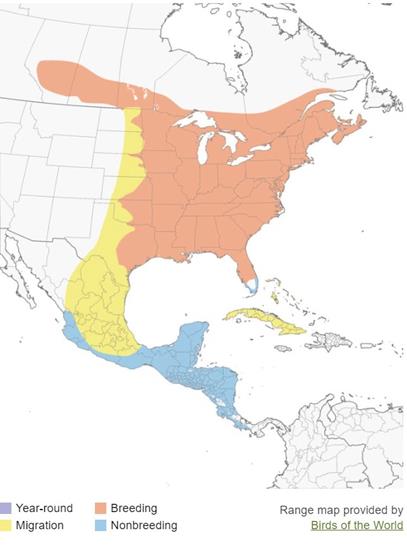

A quick look at the map on the right shows that between the wintering grounds shown in blue and the breeding grounds shown in orange lies the vast expanse of the Gulf of Mexico. Now THAT looks like a potential problem for a migratory bird!

Do hummingbirds circumvent the Gulf of Mexico or do they fly straight over it? The answer is ‘both’. Some Ruby-throats journey overland through Mexico and along the Texas Gulf Coast. Others jump from the Yucatan – that blue peninsula that juts northeast toward the U. S. – over to the islands of the Caribbean, make the short hop to Florida, then continue up the east coast. Yet a third group of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds launches from the Yucatan peninsula and flies non-stop 500 miles across the Gulf of Mexico. Risky? Yes indeed! But if successful, this daring move is the shortest journey to their breeding grounds. If all goes well, these Ruby-throats may arrive at their breeding grounds earlier and in better condition than their rivals.

Recent studies have shown that the winter range of Ruby-throated Hummingbirds has expanded northward dramatically in the past few decades. Over-wintering Ruby Throats, especially males, are now regularly seen at feeders in the southeastern U.S. as far north as South Carolina. This incremental change is probably a result of climate change, The slow northward creep of wintering Ruby-throats is expected to continue and expand as our climate gradually changes. (Flesher 2015)

So how exactly does a tiny bird that weighs a little more than a penny manage to make a 500-mile non-stop Gulf of Mexico crossing? Consider the following mind-boggling facts:

- Before the gulf crossing Ruby-throats add an additional 25 – 40% to their body weight by feasting on nectar and small insects.

- During migration, a hummingbird‘s wings flap at a speed of 15-80 beats per second.

- A migrating hummingbird‘s heart beats 1260 times per minute!

- Like most songbirds, migrating hummingbirds travel at a speed of 20 – 25 miles per hour. Thus their non-stop 500-mile transit of the Gulf of Mexico takes about 18-20 hours.

- A Hummingbird‘s average body temperature is 100 degrees. They fly mostly at night to avoid over-heating.

Ruby-throated Hummingbirds depart the Yucatan at dusk, fly through the night and into the next day. They do not soar but must flap their wings for the entire journey. There are no rest stops. Contrary winds can lengthen the trip. Once they leave radar contact with land, we have little knowledge of what the birds encounter as they cross the gulf. Birds departing Mexico at dusk should arrive at the U. S. Gulf Coast by mid-afternoon the following day.

Migrating hummingbirds begin to arrive in Maryland in early April, with the main abundance of birds arriving mid April to early May. For early arrivals, flowers and nectar may be in short supply. Hummingbirds regularly include small insects and spiders in their diets. These insects may be captured in mid air by hawking, plucked off of bark, or picked off of spider webs. Sap is also an excellent addition to a hummingbird‘s diet. While it is not as sweet as nectar from a flower, sap contains a significant amount of sucrose and can be sipped from wells drilled by woodpeckers.

Another problem faced by early arriving hummingbirds is the challenge of staying warm. How does a tiny bundle of feathers keep from freezing to death? Not to worry! Mother Nature has come up with a unique solution. Hummingbirds are able to lower their body temperature and metabolism to enter into a state of inactivity known as torpor. In fact, the birds have several levels of torpor ranging from shallow to deep. In torpor, a hummingbird‘s body temperature may drop from its normal 100 degrees F to as low as 50 degrees F. Just think, we humans normally have a body temperature of 98.6 degrees. If we were to drop even 5 degrees from this normal level, we would be in danger of death. Torpor is an energy-saving mode far more fuel efficient than sleep or hibernation.

Hummingbirds are a marvel of unique adaptations and a beauty to behold. Now that they are settled into Maryland for the summer, let’s keep them safe and healthy. In the heat of summer, sugar water ferments. Be sure to change your hummingbird food and clean the feeder every few days when the weather is hot.

As the end of the season approaches both the experienced adults and the first year birds will undertake the challenging journey southward. They follow roughly the reverse of the same route that they navigated in the spring. Young hummingbirds do not travel with their parents but are left to find their own way. Genetics usually ensures that the young birds travel a route like that of their parents; along the Texas Gulf coast, through the Caribbean or across the Gulf of Mexico. With these young stragglers in mind, leave your feeder up until at least October 1st. Be sure to leave the feeder in place until 2-3 weeks after you have seen the last hummingbird in order to provide food for late-comers. Until then, enjoy the show and appreciate the wild beauty of these feisty fliers! They are truly one of nature’s tiniest and most remarkable creations.