At Last! Lasagna That's All Natural, Organic, and ... Good for the Environment!

By Judy Ferris, Master Naturalist and Guest Blogger

ACLT’s Flower Girls are always ready to experiment. Having created their first 86-foot long flower bed in 2017 using the laborious process of double digging, they happily embraced an alternative method to create their second flower bed; a row which would be devoted to growing cut flowers. Thus, the first lasagna garden was born at ACLT’s Double Oak farm.

“A lasagna garden? What’s that?” Lasagna gardening is an unconventional method for creating an organic garden. In a nutshell, it consists of layering locally available organic material atop existing soil. As any chef will recognize, the process is somewhat akin to layering tomatoes, ricotta, pasta, and other goodies in a baking dish to create a sumptuous lasagna. Leaves collected in fall are the backbone of Double Oak’s lasagna garden. The layers also include composted horse manure, sawdust, shredded paper, Leaf-gro, weed-free and disease-free greenery, and grass clippings. Season with a sprinkling of minerals to adjust the soil Ph and nutrition.

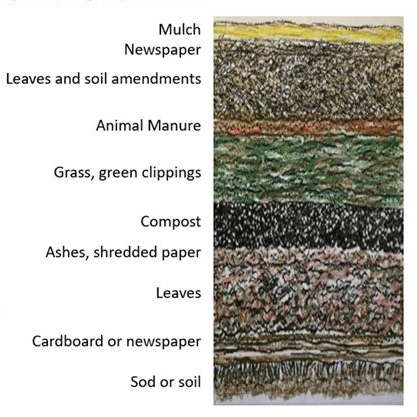

Example: Lasagna Layering

The illustration on the right is an example of materials that can be used as layers in your lasagna. But don’t worry if you don’t have all the materials readily available – stick to a 4:1 ratio of materials high in carbon and nitrogen. Aim for a total thickness of at least 18″ deep. Adjust Ph and soil nutrition as needed and your lasagna should be a hit!”

Materials High In Carbon: Leaves, Compost, Animal Manure, Hay or Straw, Sawdust, Peat Moss, Shredded Paper, and Wood Ash.

Materials High in Nitrogen: Grass Clippings, Weed- & Disease-free Clippings

After ‘baking’ for a few months, the chunky lasagna layers break down into dark, rich soil which resembles succulent crumbled brownies. A gardener’s dream! As a bonus, not only does the lasagna method create nutrient-rich soil, it also benefits our climate in a variety of ways.

- Locally available materials are used, thereby minimizing the use of plastic soil bags and the need for diesel-powered shipping.

- The lasagna method does not disturb the underlying soil community; an interwoven complex of fungi, worms, insects, plant roots, and soil particles which is essential to keeping plants healthy.

- Carbon dioxide is a heat-trapping gas in our atmosphere. By returning leaves and other organic material to the soil, we are sequestering or ‘storing’ carbon in the soil. Instead of throwing organic material away to release its carbon to become carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the lasagna method actually composts organic material. Compost captures carbon to enrich the soil and grow healthier plants.

- Last, but far from least, your body will thank you for not doing all that double-digging!

Double Oak Farm’s lasagna-method Cutting Garden has been a big success. Its rich soil produces plants that pump out gorgeous blooms month after month. The same strategy can be applied to vegetable gardens, berry patches, and herb gardens as well. Who could ask for more? If you are interested in cooking up a garden using this novel gardening technique, the Flower Girls recommend that you stop by the farm to talk to them. Or, better yet, consult Patricia Lanza’s quintessential book on the subject: “Lasagna Gardening: A New Layering System for Bountiful Gardens: No Digging, No Tilling, No Kidding!” Published by Rodale Press, 1998.

Interested in volunteering at Double Oak Farm? Or any of the other volunteer opportunities at ACLT? Visit: www.acltweb.org/index.php/volunteer to learn more and to sign up!