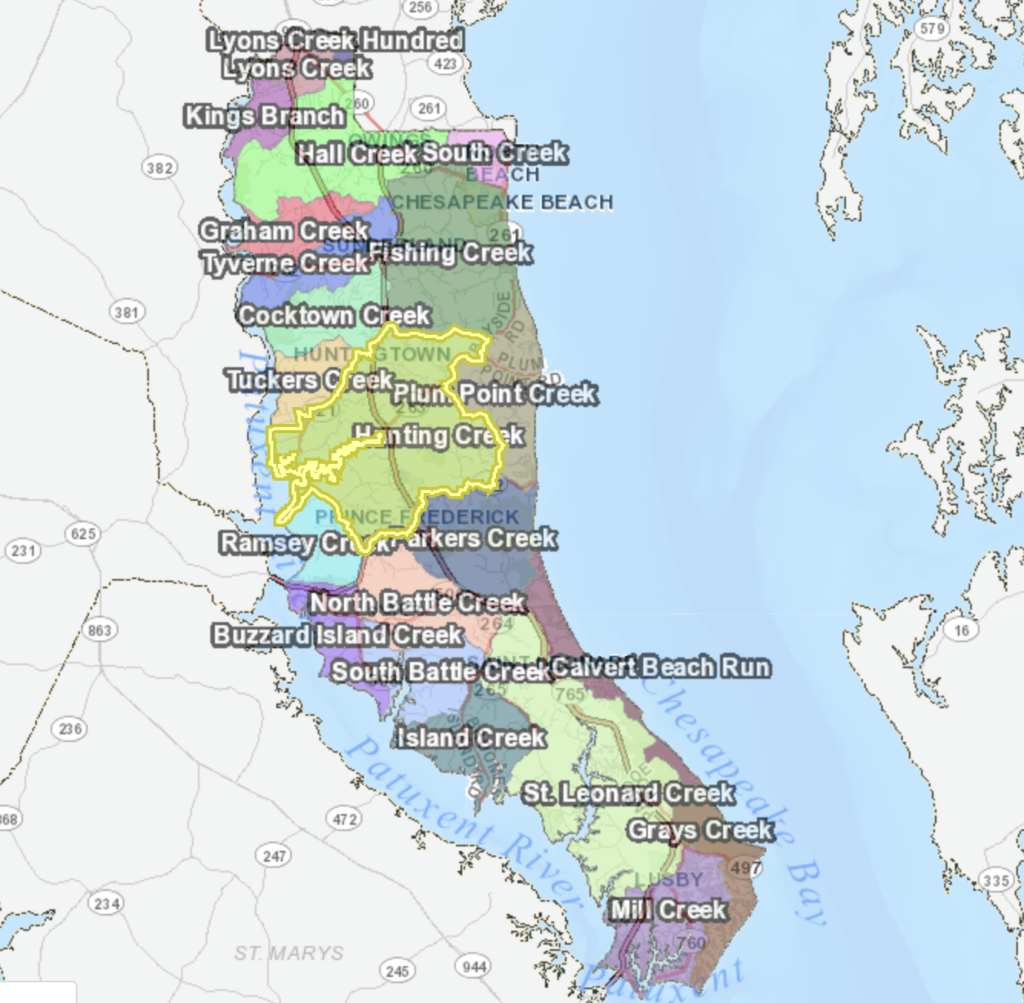

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s plan to establish a new wildlife refuge in Southern Maryland was positively received by the public at the last of three listening sessions on Tuesday, April 18th. Held at the Calvert Marine Museum in Solomons, the event was attended by mainly Calvert County residents, but the nearly full house of attendees had representation from all over Southern Maryland.

The three listening sessions have been a way for the Service to engage public input in the rollout of the plan, complying with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which requires a public scoping period. The purpose of the meetings was to inform the relevant communities about the Land Protection Plan/ Environmental Assessment (LPP/EA) being drafted for establishing a refuge, provide the rationale behind the proposed acquisition boundary, and answer any questions the public might have. While the Service was well prepared to assuage worries about the plan, such as how it might affect private property within the acquisition boundary, there was very little discourse at any of the three sessions that stemmed from criticism or concern. The reaction from the audience at Tuesday’s session was overwhelmingly positive, with most comments being inquiries about the logistics of the plan or words of support.

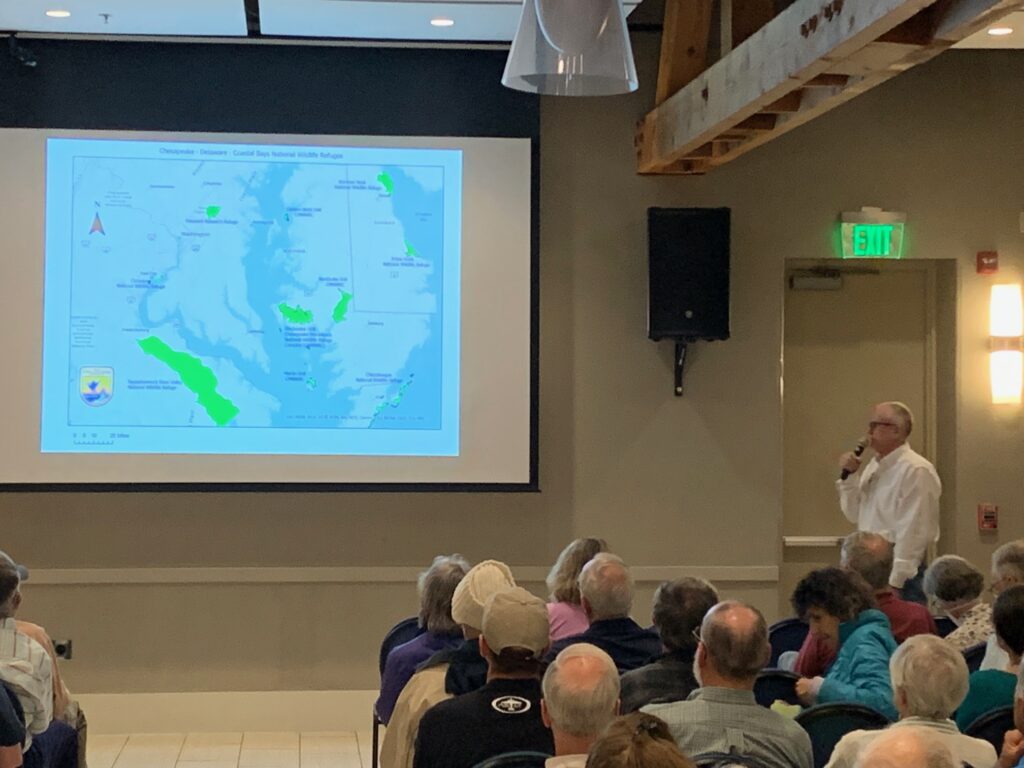

Once completed, the draft plan will be released to the public for a 45 day review period, where more comments will be welcomed. The finalized plan must be approved by the USFWS director, after which the Service may begin seeking properties from willing sellers to compose the new national wildlife refuge. See the presentation from the listening sessions here.

Now that the listening sessions are completed, the Service invites the public to send comments for consideration in the final draft of the LPP/EA.

Email: FW5southernmarylandplan@fws.gov

Project Website:

https://www.fws.gov/project/proposed-new-refuge-lands-southern-maryland